A Revisionist History of Adam Smith

What the godfather of the free market has to say about the better angels of our nature

“Economics, which was becoming an ever more abstruse science, producing mathematical treatises with no practical use, seemed almost destined as a sifting device . . . I often asked otherwise intelligent members of the prebanking set why they studied economics, and they explained it was the most practical course of study, even while they spent their time drawing funny little graphs. They were right, of course, and that was even more maddening . . . Economic theory served almost no function at an investment bank. The bankers used economics as a sort of standardized test of general intelligence.”

– Michael Lewis, Liar’s Poker

Relevant pre-reads: Of Birds and Frogs.

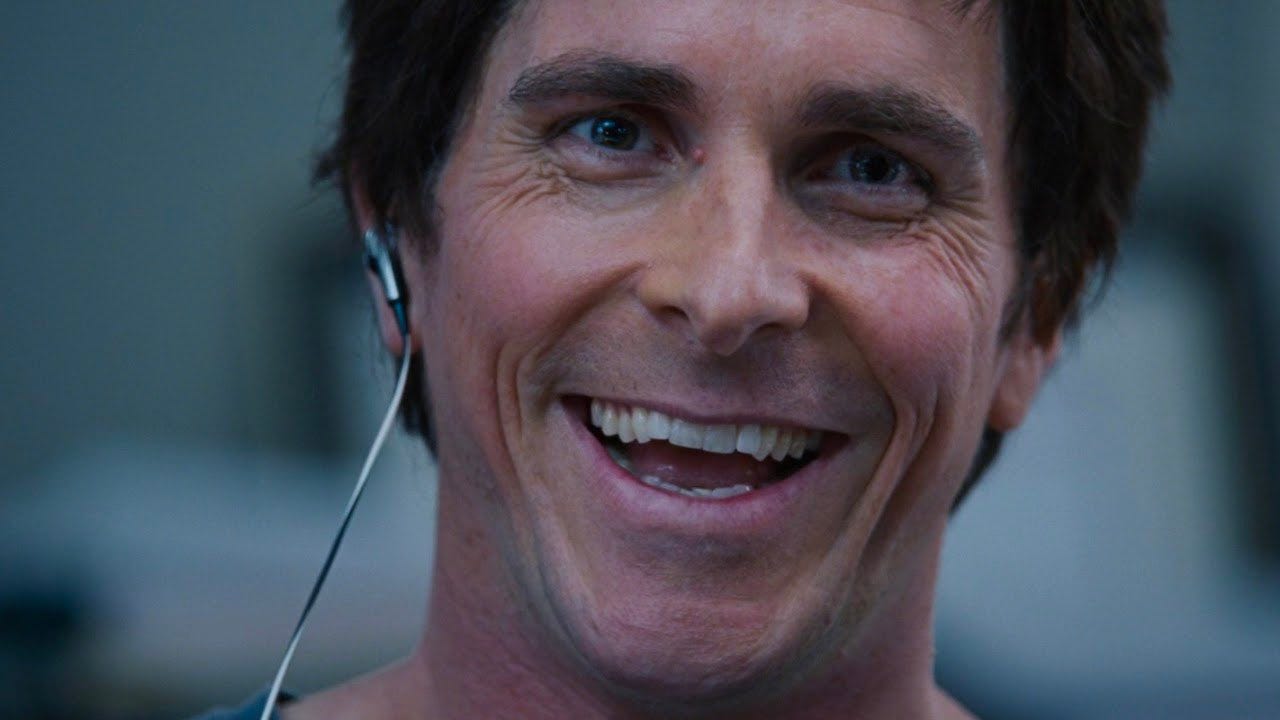

In the first scene of The Big Short, as the eccentric hedge fund manager Michael Burry blasts heavy metal and races through spreadsheets of mortgage-backed securities, the camera briefly flashes a copy of Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations on his office bookshelf. The association is clear: this is a book for quants.

Yet if alive today, Smith might be surprised that economics, a field with such literary beginnings, has become the go-to major for signaling quantitative aptitude amongst Wall Street job-seekers, as this classic of political economy contains very little math. Instead, like the early texts of any new discipline, The Wealth of Nations is a qualitative collection of personal remarks on observed phenomena, pontifications on their underlying causes, and reflections on their implications. It is full of logical reasoning but few formulas. It contains simple arithmetic but no large datasets. It wields a conceptual, philosophical tone.

He might also be surprised about the extent to which the “Invisible Hand” singularly dominates the discipline he created. This analogy, which was first introduced in this book, refers to emergent social intelligence and efficiencies produced by the division of labor among rational individuals operating in a free market and has served as the theoretical foundation of neoclassical economic thought ever since. However, this idea only constitutes a fraction of Smith’s full theory on human nature, overshadowing the less celebrated but no less significant ideas introduced in his other book: Theory of Moral Sentiments.

Moral Sentiments endows the Rational Man from Wealth of Nations with an emotional alter-ego. It is a treatise on the importance of empathy in economic relations, where Smith defines empathy as the unique human ability to relate to one another by artificially perceiving experiences through the vantage point of other minds. Aside from general intelligence, this mental faculty is the most distinguishing characteristic of our species and the facilitator of peaceful, just civilization.

Rather than quarantine moral psychology from the rest of what is now considered traditional economics, Smith believed understanding empathy was a prerequisite to deciphering the conditions under which the benefits of the rational market emerged. It is this intrinsic desire to relate to one another that tempers our violent inclinations and makes free markets possible. It also balances the potentially destructive effects that wealth inequality can impose on a society. Smith regarded empathy as a general purpose social mechanism by which a peasant may exchange resentment for the rich with appreciation and entertainment; one memorable observation from Sentiments notes how peculiar it was that commoners in Scotland at the time vicariously enjoyed the frivolity of the English aristocracy (so long as their basic needs were met) by consuming tabloids and other forms of media about their gaudy lifestyles (I think of this passage whenever I see a People magazine at the checkout counter).

With the importance Smith places on this seemingly irrational and emotional side of human nature, it stands to reason that any intellectual descendent would be keenly interested in learning its secrets and coaxing its growth. Instead, the discipline formerly known as political economy splintered off into inbred offspring like political science, economics, and sociology, forever separating the lessons of Moral Sentiments from those of the Wealth of Nations. Neoclassical economics become entirely absorbed by Homo Economicus, the perfectly rational animal, and decidedly less infatuated with the uniquely human mystery of how we can live in highly unequal, genetically diverse, anonymized groups without resorting to violence (most of the time). Insect colonies are held together by biology and act as one unified organism; human colonies are held together by a peculiar mix of empathetic and competitive social behavior amongst individuals. It is not the benevolence of the butcher that wills him to provide us with dinner but perhaps it is his empathy that enables him to loan meat to a neighbor on credit.

We rightly credit Smith for being The Godfather of the free market, the division of labor, and modern economics. But we lost half his theory: the examination of the emotionally complex and seemingly irrational side of human nature that dictates outcomes in culture, art, and religious beliefs, areas of inquiry which were cut loose and shoved into other disciplines shortly after Smith published his works. Neoclassical economics takes a peaceful, stable society as an exogenous input then holds it under a reductionist microscope whereas Smith thought the irrational and rational sides of humanity were inextricably linked. You can’t explain one without the other.

Returning to the sacred texts reveals an analytical lens with much more theoretical depth and explanatory power than the vapid textbook charts and graphs have to offer, a lens that produced theories aiming at bigger leaps towards truth, even if they were abstract, untestable and politically inconvenient at the time.

Thank you to Dr. Brian Bitar for inspiring this essay five years ago in a class titled “The Idea of the Free Market”.