Falsifiability & Knowledge Expansion

How theories evolve and when to call BS

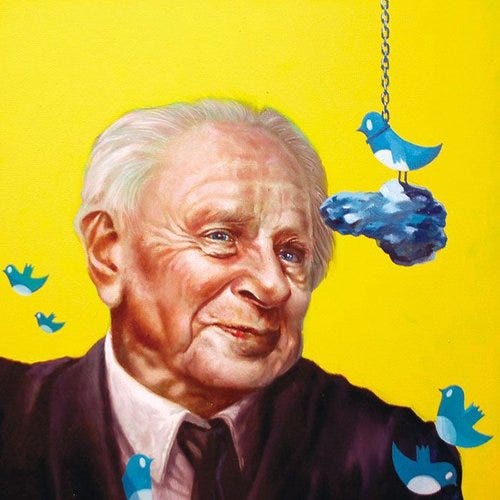

Karl Popper argues that falsifiability, or testability, is an essential input to the meticulous process of disproving scientific hypotheses – the only legitimate method of expanding knowledge.

According to Popper, truth is beyond human jurisdiction in the natural and social sciences; genuine proofs can only be attained through abstract math and logic. Although we can never definitively prove a theory is true, we may definitively prove it is false, meaning our current knowledge base is the sum of information we’ve amassed from unsuccessful attempts to disprove our best surviving theories. Survival of each theory is predicated on an evolutionary mechanism that selects for a hypothesis's resistance to invalidation via observation or experiment.

Knowledge expands by way of critical examination of conjectures (hypotheses) and possible refutations (experiments, observations) that increasingly take us farther into the infinite unknown and closer to, but never intersecting, truth. The act of “doing science” refers to a tradition of critical discussion where participants iteratively create hypotheses then ruthlessly search for invalidation. All hypotheses are guesses, and the best scientists seek to detect the errors within their guesses.

As such, the quality of any scientific theory is dependent upon the extent of its falsifiability: whether the predictions of its hypotheses can be measured and the relative ease of devising tests to this end. Theories with a methodological aversion to falsehood – when experimental data or observation cannot reasonably be attained – are not scientific. For example, the hypothesis that a young boy is subconsciously sexually attracted to his mother cannot be disproven by observation or experiment, and is therefore not scientific. A similar dynamic is common in theories of political economy as the many holistic, utopian hypotheses generated by social scientists cannot actually be tested without fully redesigning a society according to the theoretical blueprint. The uncertainty caused by a lack of experimental data can aid authoritarianism because the sponsor theorist can always claim that the experiment has not gone far enough in its implementation, which is the only avenue to generating definitive conclusions. The greater the theory, the greater the consolidation of political power required to run the experiment.

However, limiting theories to those that can easily be tested would stall knowledge expansion; useful theories must also purport to explain more by reaching deeper into the unknown and encouraging the reconsideration of existing theories. In this way, they require a heavy dose of creativity by painting a world that might exist but evades perception, thus proposing new avenues into the unknown.

The best theories maximize the trade-off between ingenuity and testability. Newton and Einstein took big swings and advanced our collective knowledge to a remarkable degree, yet both were eventually disproven. They were not powerful despite their ability to be disproven, but precisely because they could logically be disproven and actively sought to do so.

The best scientists exhibit a steadfast awareness of human fallibility, a vigorous imagination, relentless adherence to method, and an inclination towards critical discussion. The quality and openness of this discussion is one of the most important barometers of a healthy civilization.

Beware of theories that cannot be tested and those averse to self-critical examination.